In India, “The Emergency” refers to the 21-month period from 1975-1977 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had a state of emergency declared across the country. Officially issued by President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed under Article 352 of the Indian Constitution because of the prevailing “internal disturbance”, the Emergency was in effect from 25th June 1975 until its withdrawal on 21st March 1977. The order bestowed upon the Prime Minister the authority to rule by decree, allowing elections to be suspended and civil liberties to be curbed. For much of the Emergency, most of Indira Gandhi’s political opponents were imprisoned and the press was censored. Several other human rights violations were reposted from the time, including a forced mass- sterilization campaign spearheaded by Sanjay Gandhi, the Prime Minister’s son. The Emergency is one of the mist controversial periods of Independent India’s history. The final decision to impose an emergency was proposed by Indira Gandhi, agreed upon by the president of India, and thereafter ratified by the cabinet and the parliament, based on the rationale that there were imminent internal and external threats to the Indian state.

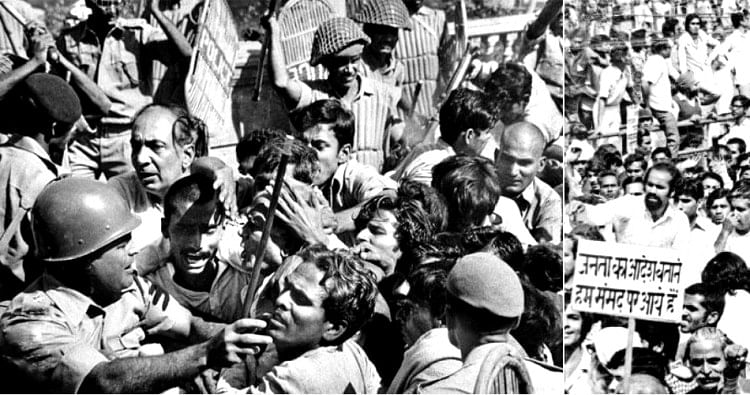

On the night of 25th June 1975, the president on the orders of Indira Gandhi declared emergency. After midnight, the electricity to all major newspaper offices was disconnected. In the early morning, a large number of leaders and workers of the opposition parties were arrested. The Cabinet was informed about it at a special meeting at 6 am. On 26th June, after all this had taken place. This brought the agitation to an abrupt stop; strikes were banned; many opposition leaders were put in jail, the political situation in the country became really quite yet tense. Deciding to use its special powers under the Emergency provisions, the government suspended the freedom of the press. Newspapers were asked to get prior approval for all the materials to be published. This is known as press censorship. Apprehending social and communal disharmony, the government banned Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and Jamait-e-Islami. Protests and strikes and public agitations were disallowed. Most importantly under the provisions of Emergency, the various fundamental rights of the citizens stood suspended, including the right of citizens to move the court for restoring their fundamental rights.

The government made extensive use of preventive detention. Under this provision, people are arrested and detained not because they have committed any offence, but on the apprehension that they may commit an offence. Using preventive detention acts, the government made large scale arrests during the Emergency. Arrested political workers could not challenge their arrest through Habeas Corpus petitions. Many cases were filed in the high courts and the Supreme Court by and on behalf of the arrested persons, but the government claimed that it was not necessary to inform the arrested persons of the reasons and grounds of their arrest. Several high courts gave judgements that even after the declaration of emergency the courts could entertain a writ of habeas corpus filed by a person challenging his/her detention. In April 1976, the constitution bench of the Supreme Court over-ruled the high courts and accepted the government’s plea. It meant that during Emergency, the government could take away the citizen’s right to life and liberty. This judgement closed the doors of judiciary for the citizens and is regarded as one of the most controversial judgements of the Supreme Court.

There were acts of dissent and resistance to the Emergency. Many political workers who were not arrested in the first wave, went ‘underground’ and organised protests against the government. Newspapers like the Indian Express and the Statesman protested against censorship by leaving blank spaces where news items had been censored. Magazines like the Seminar and the Mainstream chose to close down rather than submit to censorship. Many journalists were arrested for writing against the Emergency. Many underground newsletters and leaflets were published to bypass censorship. Kannada writer Shivarama Karanth, awarded with Padma Bhushan, and Hindi writer Fanishwarnath Renu, awarded with Padma Shri, returned their awards to protest against the suspension of democracy. The Parliament also brought in many new changes to the Constitution. In the background of the ruling of the Allahabad High Court in the Indira Gandhi case, an amendment was made declaring that elections of Prime Minister, President and Vice-President could not be challenged in the court. The forty-second amendment was also passed during the Emergency. You have already studied that this amendment consisted of a series of changes in many parts of the constitution. Among the various changes made by this amendment, one was that the duration of the legislatures in the country was extended from five to six years. This change was not only for the Emergency period, but was intended to be of permanent nature. Besides this, during an Emergency, elections can be postponed by one year. Thus, effectively, after 1971, elections needed to be held only in 1978; instead of 1976.

Controversies during the emergency-

Emergency is one of the most controversial episodes in the Indian Politics. One reason is that there are differing viewpoints about the need to declare emergency. Another reason is that using the powers given by the constitution, the government practically suspended the democratic functioning. As the investigations by the Shah Commission after the Emergency found out, there are varying assessments of what the lessons of Emergency are for the practice of democracy in India. The actual implementation of the Emergency is another contentious issue. The government said that it wanted to use the Emergency to bring law and order, restore efficiency, and above all, implement the pro-poor welfare programmes. For this purpose, the government led by Indira Gandhi announced a twenty-point programme and declared its determination to implement this programme. The twenty-point programme included land reforms, land redistribution, review of agricultural wages, worker’s participation in management, eradication of bonded labour, etc. in the initial months after the declaration of Emergency, the urban middle classes were generally happy over the fact that agitations came to an end and discipline was enforced on the government employees. The poor and rural people also expected effective implementation of the welfare programmes that the government was promising. Thus, the different sections of society had different expectations from the emergency and also different viewpoints about it.

Critics of Emergency point out that most of these promises by the government remain unfulfilled, that these were simply meant to divert attention from the excesses that were taking place. They question the use of preventive detention on such a large scale. Many prominent leaders were arrested. In all, 676 opposition leaders were arrested. The Shah Commission estimated that nearly one lakh eleven thousand people were arrested under the Preventive Detention Act. The Shah Commission report mentions that the General Manager of the Delhi Power Supply Corporation received verbal orders from the office of the Lt. Governor of Delhi to cut electricity to all newspaper presses at 2 am on 26th June 1975. Electricity was restored two to three days later after the censorship apparatus had been set up. Emergency is described as the darkest phase of the Indian Politics.