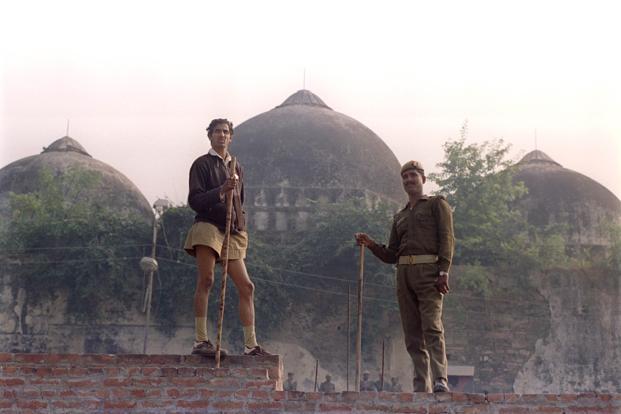

Babri Masjid was built in 1528 by Mir Baqi, a commander of Mughal emperor Babur. The Ayodhya dispute revolves around access to a site traditionally regarded among Hindus to be the birthplace of the Hindu deity Rama and the history and location of the Babri Mosque which was allegedly built after demolishing a Hindu temple. In 1885 Mahant Raghubirdas filled a plea in the court to build a canopy outside the monument and offer prayers which were rejected. Later another petition was filled by Gopal Simla and P. Ramachandra seeking the right to pray when idols of Lord Rama mysterious appeared inside the monument. This was followed by religious bodies Nirmohi Akhara and UP Sunni Waqaf Board moving the court for possession of the site. Though in 1986 the Faizabad court ordered the opening of the site for Hindu devotees to offer prayers, the demolition of the Babri masjid monument by karsevaks brought a dramatic turn to the events. The government got directly involved in the matter after passing of the ‘Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act’ by Centre for the acquisition of disputed land by the government on April 3. Basically, it is a title entitlement suit i.e. who actually owns the property. Read here is it true that a temple was demolished for the construction of Babri Masjid?

What was the judgement given in Ismail Faruqui case?

It was at this point that various writ petitions, including one by Ismail Faruqui, filed at Allahabad HC challenging various aspects of the Act. SC had said in the historic Ismail Faruqui case that a mosque was not integral to Islam. This verdict is also broadly read as SC’s view on the case as a whole. But beyond Ayodhya, the judgement in the Ismail Faruqui case is far from being in accordance with any secular republic’s mandate to preserve the sanctity of places of worship. What makes the verdict important and historic is its relation to the main lawsuit. In the minority view of Justice Bhushan acquisition of the disputed Ayodhya land in the name of preserving public order is constitutionally impermissible. When a place of worship of a particular religion is attacked by the majority religion and public order is threatened, the prime duty of the government is to save the structure and not to acquire the property for the sake of preserving order.

The verdict given by Allahabad court on the dispute in 2010

SC in an interim order under the 2003 Aslam Bhure Case ordered that no religious activity of any nature be allowed at the acquired land and should be operative till disposal of the civil suits in Allahabad HC to maintain communal harmony. On September 30, 2010, the Allahabad High Court pronounced its verdict on four title suits relating to the Ayodhya dispute, in a 2:1 majority, it was declared that three-way division of disputed area will be done between Sunni Waqf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara and Ram Lalla. SC on May 9, 2011, put the HC verdict on Ayodhya land dispute on hold.

Pleas submitted in the court in the court

After nearly 5 years of the SC stay order Subramanian Swamy files plea in SC seeking construction of Ram Temple at the disputed site. Following which SC constituted a three-judge bench to hear pleas challenging the 1994 verdict of the Allahabad HC. It also directed the Chief Justice of the Allahabad HC to nominate two additional district judges within ten days as observers to deal with the upkeep of the disputed site. UP Shia Central Waqf Board tells SC temple can be built in Ayodhya and mosque in Lucknow, in a Muslim-dominated area at a reasonable distance from the disputed site. Thirty-two civil rights activists file plea challenging the 2010 verdict of the Allahabad HC. In 2018 SC started hearing the civil appeals.

But it eventually rejected all interim pleas, including Swamy’s, seeking to intervene as parties in the case.

Why is the SC is not willing to refer the case to a larger bench?

A three-judge SC bench with 2/1 majority on Sunday came to declare that unnecessary controversy is being sought to be created by broadly interpreting the verdict in the Ismail Faruqui case. The judgement, according to the bench, affirmed that since namaz can be offered anywhere and the mosque isn’t really an “essential” requirement. After rejecting a string of pleas asking for readjudication of the judgment given in this case, the SC bench including Dipak Mishra held that no case is made out in order to go back to the judgement. CJI Mishra and Justice Bhushan held that the court had made the comment to dispel any doubt or argument that mosques had immunity against the acquisition of their land by the Central government for public welfare. Justice Bhushan went on to say that in fact, no such immunity is enjoyed by any religious structures whatsoever under the sovereign powers of the government act. Therefore there is no relation or influence of the Faruqui verdict with the main lawsuit.

Should closure be sought between the Babri Masjid-Ram Janmbhoomi and the Ismail Faruqui case?

Justice Abdul Naseer’s dissenting verdict tells us how the Ismail Faruqui Case influenced the Allahabad court verdict. Religious practices were determined without any detailed examination of religious tenets in 2010 in the same way as it was in 1994. The court should also base its decision only and only on civil laws and rights and stay as much far removed as possible from religious arguments. The dismissal of the pleas and the 1994 judgement opens up the opportunity for a renewed interpretation of the 1994 case. But we must also see that if the Ayodhya lawsuit is referred to a larger bench, would give political oxygen to the case as views and opinions of more jurists would help in arriving at the best decision possible. Since the ball is finally in SC’s court only, let us wait for 29th October and hope for the best.